With the precision of a blade

Carmen

The Australian Ballet

Friday 7th March, 2025

Saturday 8th March, 2025

Regent Theatre, Melbourne

Choreography: Johan Inger

Assistant choreographers: Toby Mallitt, Javier Rodríguez Cobos and Urtzi Aranburu

Dramaturg: Gregor Acuña-Pohl

Music: Rodion Shchedrin, after Georges Bizet, “Carmen Suite”

Georges Bizet, orchestrated by Álvaro Domínguez Vázquez, “Overture” and “Danse Bohème”

Additional original music: Marc Álvarez

Lighting design: Tom Visser

Set design: Curt Allen Wilmer and Leticia Gañán (aapee) with Estudio DeDos

Costume design: David Delfín

Costume design associate: Maria Luisa Ramos

With Orchestra Victoria

Crime of Passion, my response to The Australian Ballet’s Carmen, drawn up especially for Fjord Review.

Cold, immovable violence is rooted at the heart of Johan Inger’s Carmen. Drawing from Prosper Mérimée’s 1845 novella, Inger’s timeless version of Carmen revels, as it was originally written[i], Carmen’s death, at the hands of Don José, as chillingly intentional. In Inger’s hands, her death is no operatic, heated crime of passion, and, consequently, he, too, displays his original source material in an unapologetically matter-of-fact way. On opening night at The Regent Theatre, The Australian Ballet took up this renowned tale with the precision of a blade, Nijinsky still warm in the wings.

Just as Mérimée’s novella is compact[ii] for the epic narrative it contains, Inger’s Carmen utilises rapid turns to destabilise the reader-cum-audience, over two swift acts, as it unfurls at breakneck pace. But what to do with the disturbing epigram which lies, untranslated in Greek, at the beginning of the novella[iii]? It is part of the tame-and-control violence. As Inger comments, “you have to ask yourself: why do I want to do it?”[iv] As such, Inger presents a Carmen which he feels addresses male violence against women. The underlying, repeating pattern is tragic. “I’m trying to communicate something… I’m trying to move you”[v]. And move me it does.

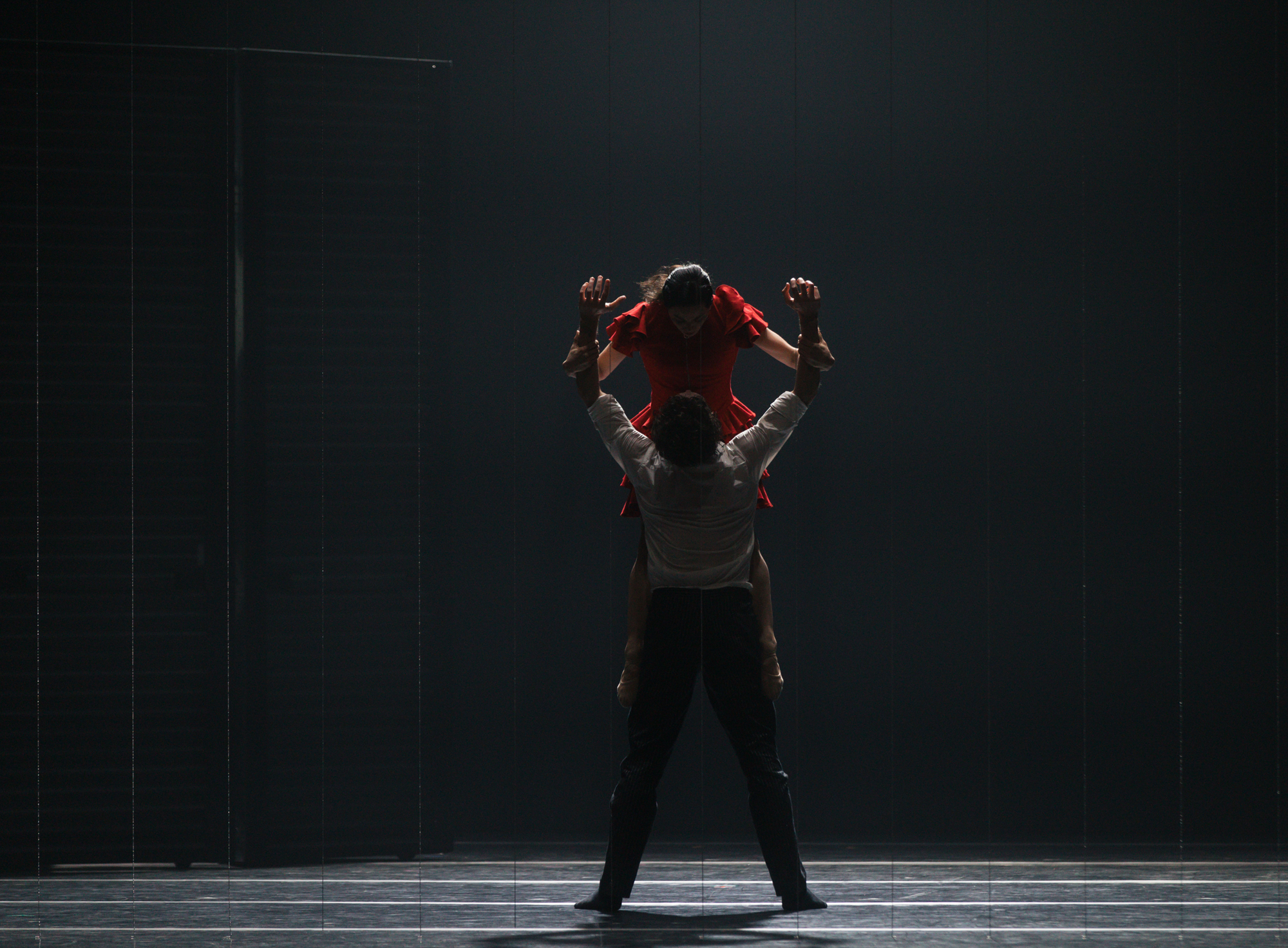

The violence of Carmen both obdurate and indispensable, in order to present a new way of entering the story, Inger has added the role of the Boy, played with lightness and intrigue by Lilla Harvey on opening night. In white shorts and top, Harvey begins as the innocence of youth, guiding the audience through the ballet. The role of the Boy left open to interpretation or fluid, Harvey “could be Don José as a child, … or the unborn child of Carmen and Don José, or anyone of us, … wounded by an experience of violence”[vi]. The right to exist without fear is unmistakable, and driven home with such clarity when portrayed as a dream sequence in the second act as Carmen, Don José and the Boy spring into ‘happy family’ action. Bathed in a warm golden light, one small part nostalgia, to a sizable chunk of fantasy, Jill Ogai’s Carmen and Callum Linnane’s Don José, leap from their reality and appear airborne in their delight. The speed of this transition is frightening and effective as they enact a Sunday drive. The bright personas of make-believe the three adopt, so convincing it is heartbreaking.

Ogai’s Carmen is defiant to the last. In the face of death, she holds to her principles. Unzipped, released from her costume, her red dress remains, and it is this that Don José clutches at the end; it is not her, but a veil, and, consequently, her spirit remains free. Inger’s choreography presents a Don José responsible for his own actions, as opposed to one which asks women be held accountable for men’s behaviour. Linnane’s Don José appears suitably as if having throttled the light from every part of himself, but for the aforementioned ‘happy families’ puppet-like mirage. Upright, uptight, and stifled, upon arrival, crumpled and ashen faced, by close, Don José is representative of social order and Carmen, very much outside of society, her non-conformity threatening the preferred narrative order, or so say the powers that be. Through a rawness and clarity of movement, Ogai meets the voyeuristic gaze in her eternal resistance to domination; the social body ever loves to expel the desirable but dangerous Carmens of this world.

As Ogai describes, Inger’s Carmen, particularly where Carmen and Don José are concerned, is “like watching conversation through movement … that sits on a beautiful plane”[vii]. The stage beneath them serving as a magnet to which various parts of their bodies are drawn or glide upon, from Carmen’s legs and upper body raised defiantly in the air or Don José’s as his head and chest is dragged to the floor, seemingly beyond his control. The same magnetism, naturally, could be said to course through the two of them as well, as typified by their face-to-face deep second position plié, with their arms making triangles overhead, their hands fanning and rummaging in the air, framing their faces. As they each bend sideways, it is impossible in this courtship dance to say who is mirroring who, for it feels free and innate.

Bringing humanity to the fore with unmannered straightforwardness and raw nakedness irradiates the strength of Carmen. In contrast to the Shadows who pull strings like puppeteers, Carmen, against the odds, remains her undiluted, powerful self. The Shadows, dressed head to toe in black, like the Boy, can be read multiple ways. Through a deliberate ambiguity of meaning, they reveal the inner workings of the minds of the various characters, and, as symbols of violence, rattle percussive bones the next.

Designed by Curt Allen Wilmer and Leticia Gañán (aapee) with Estudio DeDos, the ingenious flexibility of the set, which can be configured to make a forbidding concreate wall, a mirrored ring for Marcus Morelli’s Torreo to slice into shards, a cityscape, and a mountain range through which to run, also gave me room to add my own reading. Though I was already hooked by the lure of Georges Bizet’s score, particularly the live version as performed by Orchestra Victoria, the freedom to do so, a part of the entrancement of Carmen in her many tellings[viii].

[i] A delighter of literary hoaxes, French writer Prosper Mérimée’s Carmen was originally published with no indication it was a fictional account of jealousy and murder among the Romani in Spain, in the travel journal La Revue des deux Mondes.

[ii] Mérimée’s Carmen was created in response to an even briefer epic, Pushkin’s poem, The Gypsies, which he also translated from Russian into French.

[iii] Mérimée’s opens Carmen with an epigram from Palladas, from the 4th Century AD, often translated as “Woman is a pain. There are only two occasions when she’s not: in bed — and dead.”

[iv] Johan Inger on the process of creating Carmen, ‘Johan Inger on Carmen’, TO Live YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlx16yLB4wE, accessed 6th March, 2025.

[v] ‘Johan Inger on Choreographing Carmen’, The Australian Ballet YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rx1qDdoT0VU&t=8s, accessed 7th March, 2025.

[vi] Johan Inger, Carmen, https://www.johaninger.com/#/carmen, accessed 7th March, 2025.

[vii] Jill Ogai in interview, ‘Dancing the lead roles in John Inger’s Carmen’, The Australian Ballet YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GI4Njnlxe1o, accessed 8th March, 2025.

[viii] Returning again the following night, I was fortunate to see a different cast. This time, Lilla Harvey was in the role of Carmen, and Marcus Morelli as Don José. They, in turn, opened up new readings of the characters, with different vulnerabilities brought to the fore.

Friday night cast

Carmen: Jill Ogai

Don José: Callum Linnane

Toreo: Marcus Morelli

Zúñiga: Brett Chynoweth

Boy: Lilla Harvey

Manuela: Larissa Kiyoto-Ward

Saturday night cast

Carmen: Lilla Harvey

Don José: Marcus Morelli

Toreo: Jake Mangakahia

Zúñiga: Timothy Coleman

Boy: Samara Merrick

Manuela: Belle Urwin

Image credit: The Australian Ballet’s Jill Ogai as Carmen and Callum Linnane as Don José in Johan Inger’s Carmen by Kate Longley