“Again the pigeons go round the square”

Paris, rewound

September – October 2019

11th October:

An appointment at Atelier Clot, Bramsen & Brunholt, with Christian Bramsen to see their lithographic workshop in flight, a bright injection of yellow on the rollers when we arrived, was a joy befitting the colour. The workshop, founded in 1896 by Auguste Clot, was “from the beginning known as the finest art printer in Paris. Here the young “Nabis”-artists had their lithographs printed — among others Vuillard and Bonnard — but also Degas, Munch, Cézanne, Sisley, Rodin, Matisse, and later Asger Jorn, Alechinsky, Bjørn Nørgaard and others” (Lisbeth Bonde, The French Clot-nection). The workshop is 300 square metres with a basement 80 square metres, of which we were able to explore. Down the steps, in the caves below, a well, down further still, an etching press for artists “who are perhaps a little more shy”. Atop it sits the 'memento mori' of previous artists from Mexico. The premises in Rue Vielle du Temple has three hand presses: “ 1 copper printing press. 1 lithographic Voirin press. 1 paper cutter. 250 lithographic stones (about 15 tons). 3 inkjet printers 44”, and 1 inkjet printer 60”. An archive of more than 6000 lithographs of over 500 artists”. And there we were, upon Jim’s recommendation (thanks @jim.pavlidis!), drinking beer at the table. Some three hours later we looped back to the Pompidou to meet @pasadenamansions, drawing in her sketchbook before the Francis Bacon pink, orange, and green retrospective, which earlier Christian described as “the show of the year”. Thank-you for showing us your workshop, sharing your time, making us feel so welcome, and allowing us to swim in intense colour that has been pushed into the paper, Christian. An injection of inspiration for new things to come!

(Image credit: Atelier Clot, Bramsen & Brunholt, @atelier.clot)

12th October:

“Again the pigeons go round the square. What triggers this unified movement? .... it seems completely gratuitous: the birds suddenly take flight, go round the square and return to settle on the district council building’s gutters. It is two twenty.”

Georges Perec’s catalogue of things and thoughts, his “infraordinary” written over three days in 1974 (the 18th, 19th and 20th of October) within An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris. He noted “tens, hundreds of simultaneous actions, micro-events, each one of which necessitates postures, movements, specific expenditures of energy,” and the weather: Day 1 is “Dry cold. Gray sky. Some sunny spells”; Day 2, “Fine rain, drizzle”; and Day 3 is “Rain. Wet ground. Passing sunny spells.” I wonder where and how my own mental catalogue will appear, in a collage, or on the pages of our next artists’ book. Will there be the ducks at the grotto, too low and camouflaged by the water to feature in the tourist photos of the fountain at the Jardin du Luxembourg? The stray cat interested in marking the parked Paul’s van at the entrance to the château? A man with his petite chien out for a stroll; his coffee-coloured trousers complementing the dogs orange lead and silky terrier coat. A line in the Post Office; the sun behind the teller causing me to squint. Out in the street, a euro shining, wedged in the grill; you’d need a pair of tweezers or nimble fingers to retrieve it from its hold. A loud man on his mobile. Two people on a scooter. “Four children. A dog. A little ray of sun. The 96. It is two o’clock.”

12th October:

At the Centre Pompidou. Before Joan Miró’s Blue triptych created out of “a very great inner tension, to reach the emptiness”; Raoul Duffy’s Le Dromadaire; Natalia Gontcharova’s À propose de la personne; and André Bauchant’s Fleurs variées. Before old favourites, and new favourites. For as long as the legs would hold, and not long enough at all. “Brushing a cosmic space punctuated by lines and signs of movement.” At Bacon: Books and Painting, with the “great poets [those] incredible triggers of images, their words .... open the doors of my imagination”.

(@centrepompidou)

* * *

In awe of the the Carrion crow (Corvus corone linné) and their power to “act like ink-blot tests drawing images out of my unconscious” (Mark Cocker, Crow Country). At the Jardin des Plants, the gardens are protected by the most robust and intelligent of birds, with one even walking the whole length of the pathway with us. A protector of the garden, hurrying us out the gate before the heavy downpour. We leapt on a 63, bound for Odéon, not as wet as we’d otherwise have been. A wise and beautiful bird, indeed. Merci.

* * *

There, a Rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri), not on a vase or in a painting, but on a sunflower. In the Jardin Écologique, in Paris, and her suburbs, living, glowing, green.

* * *

Following the line work of memory and movement (and avoiding the large knots of tourists, where possible, with @pasadenamansions) at the Grand Palais for the room-after-room Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec retrospective, co-curated with the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie and the Réunion des musées nationaux and supported by the city of Albi and the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec.

“.... to adore nights more than days — to adore and to detest immensely; to squander much of one’s substance in riotous living, to have a terribly direct eye and as direct force of hand; to be capable of painting certain things which have never yet existed for us on the canvas....”

— Arthur Symons, From Toulouse Lautrec to Rodin (London: 1929)

12th October:

We return by way of a silvered Maharajah recorded by Man Ray (Modern Maharajah: a Patron of the 1930s at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs), wave a wing at Constantin Brancusi’s Bird in Space (especially for @peterhaby), and a boat named ‘Louise’ (if only).

13th October:

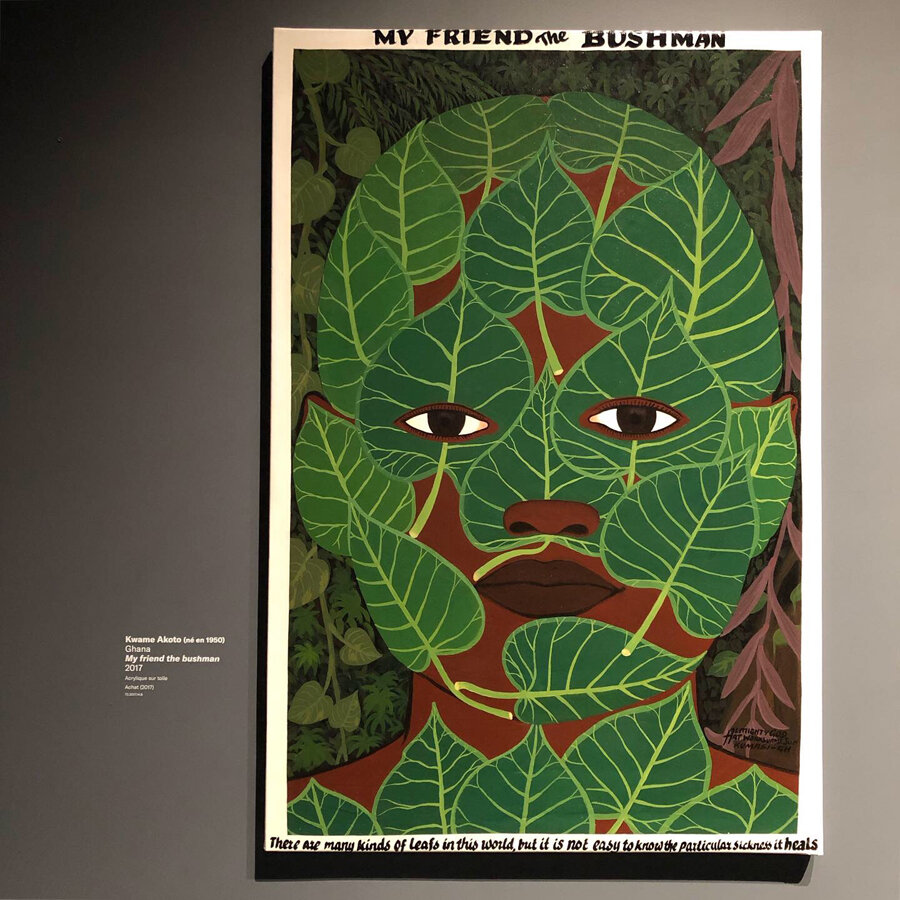

At the Musée du quai Branly — Jacques Chirac, by way of the 63 bus, before “200 hundreds years of history, enrichment, study and conservation of public collections. [The Museum] conserves almost 370,000 works originating in Africa, the Near East, Asia, Oceania and the Americas which illustrate the richness and cultural diversity of the non-European civilisations from the Neolithic period (+/-10,000 B.C.) to the 20th century”. Before private archives donated since 1998 from “30 collections representing 110 linear metres of documents .... [a] galaxy of documents [that] opens up avenues to enhance the biography of items, from their original source to their arrival in the museum”. Travel images, photographs from Burkina Faso in the ‘70s, textiles, gold, feathers, meaning and message, role, and beauty, and the paper funerary simulacra of Taiwan, “which are burnt to assure the comfort of the dead in the beyond”, such as a smartphone with special ‘paradise’ applications.

(@quaibranly)

* * *

Liquid Loft performed a fusion of Foreign Tongues and Stand-Alones for the reopening of the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. “In the Foreign Tongues projects series, Liquid Loft explore the complex interactions between verbal messages and their physical attributes. Foreign Tongues approaches, with the vocabulary of body language, the often contradictory forms of communication. Starting point for the various performances are language recordings, which were produced as part of personal interviews in different regions of Europe. ...The site-specific performances are based on local languages and jargons, reflecting the sound environment of the place. With every location, the Spoken Word Symphony grows, the characteristic architecture of the site becomes the scenery of the play”. Merge this with the acoustically interwoven solos in Stand-Alones “in separately accessible rooms [which] grow together over the course of the performance into a choreographic canon ... [as] the performers move, apparently without link to the outside world ... surrounded only by the mysteries of the mental spaces of their own world experience. ... When our senses can no longer keep up processing the upheavals in the world, the obvious becomes questionable, unnatural, vulnerable. ... [Before Bonnard, de Chirico, Picabia, Raoul Dufy, and the Delaunays] the individual becomes divided, the body a last refuge. Only in phases of smoldering silence and slow-motion can we detect the traces of expressive distortion in it”.

(@liquidloft)

Image credit: Agnès Varda working on her first feature film, La Pointe Courte, in 1954. Varda “delights in contrasts—between light and dark, wood and metal, life and death (fish and cats)—and parallels such as between the Parisian and the local young couples” (‘La Pointe Courte: How Agnès Varda “Invented” the New Wave’, Ginette Vincendeau, The Criterion Collection).