A Weight of Albatross

A new commission, in progress

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

A Weight of Albatross

2018

Realm

Maroondah City Council’s new library, cultural, knowledge and innovation centre Ringwood Town Square, Victoria

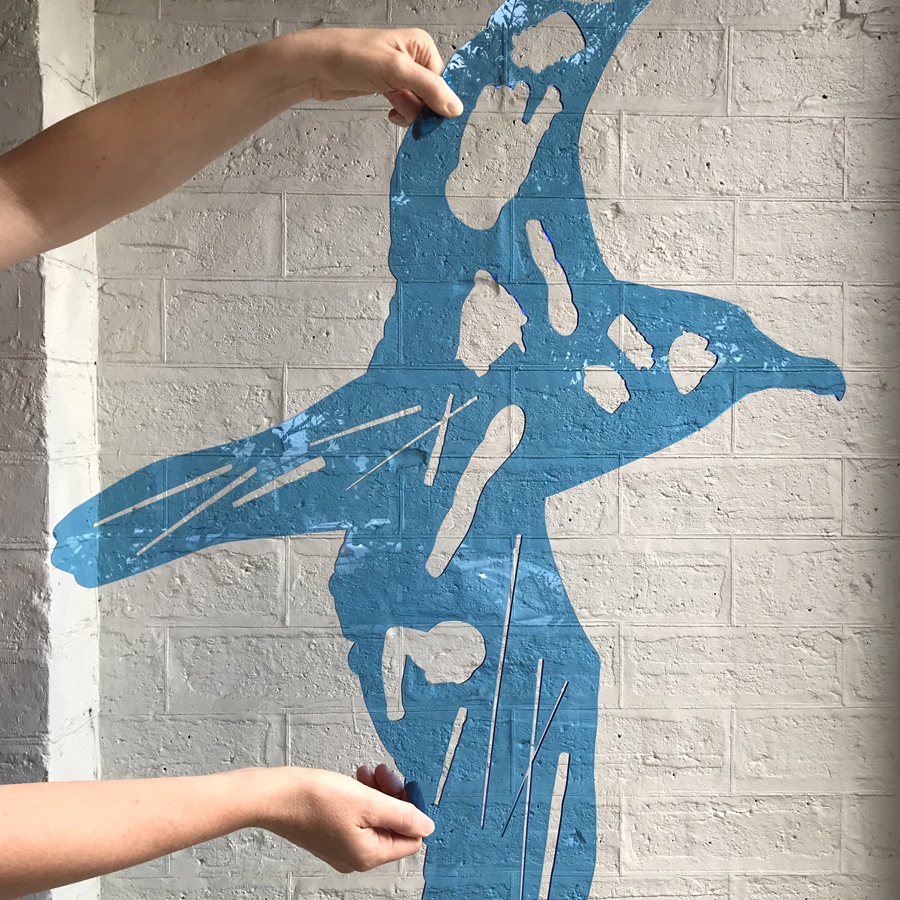

Figuring out the centre of gravity. Allowing the flow of force to be uninterrupted. Playing with the strength of a circle, making the outside lines smooth curves in place of sharp angles. Placing internal pieces to follow the line of the form while not compromising the material’s strength, and perhaps call to mind a skeleton as well as ingested debris. In order to make a weight of albatross soar, engineering is required. In order to make them hover mid-air, and be safe and secure, laser-cut from sheets of coloured Perspex, such things need to be factored in and revised.

As we tweak our albatross, widening gaps within and simplifying awkward nooks, this challenge is one we are relishing. To be suspended from a single fixing, our (intended) weight of albatross cannot weigh more than 50 kilograms. They need to be durable and lightfast, and not clack into one another. They need to move on swivels, without compromising the materials’ strength. They need to be high overhead so you cannot touch them. Their silhouettes have been organised in tiers from overhead (revealing their undercarriage) to eye-line and a little below (revealing their backs and the top of their wings).

A Weight of Albatross is a commission we are currently working on for Maroondah City Council.

This new work, created in response to the space, will be installed in May, at Realm, Maroondah City Council’s new library, cultural, knowledge and innovation centre (within Ringwood Town Square, opposite the Ringwood Station and alongside Eastland shopping centre). When we were invited to make a work for the atrium at Realm, we realised that the materials we planned to use were all manmade and that in using such materials we were contributing to pollution through manufacturing, and the creation of yet more plastic. The true cost of the materials was something we wished to incorporate into our work, and so, A Weight of Albatross was hatched: plastic to talk about durable, deadly, yet visually beautiful, plastic.

Treating sheets of Perspex and stainless steel as if they are large sheets of paper, we are in the process of laser-cutting giant collage pieces in order to create a swirl of movement, a treasure of colour, a collection of jewel-like silhouettes, in flight, soaring. All along keeping each piece in the puzzle in balance with its neighbours and the surrounding space. A change to one piece is a change to all, and no part of this ‘collage’ can be successfully altered unless thought of as a whole.

The most common collective noun for a group of albatross is a rookery, but a weight is also accepted, and though the OED preferences albatrosses as the plural, Collins and Merriam-Webster are happy to fly with albatross. So a weight it is, A Weight of Albatross, because it sounds more poetic to our ears.

With the highest concentration of plastic in birds found in populations in southern Australia, South Africa, and South America — where coastlines are closest to loosely-concentrated collections of ocean debris in the southern Pacific, southern Atlantic, and Indian Oceans — our soaring albatross will reveal the plastic they have ingested.

Suspended from the top two, perpendicular, polished stainless steel albatross will be fourteen smaller albatross all cut from frosted Perspex not dissimilar in surface texture and appearance to sea-worn glass and plastic pieces. Our Perspex albatross will hang from four lines dropped from the outstretched, unbending, stainless steel wings. Within each laser-cut albatross silhouette, what at first glance might appear like the directional strokes of feathers or skeletal framework will actually be a tangle of shapes evocative of the plastic debris the birds have ingested, including "bags, bottle caps, synthetic fibres from clothing, and tiny rice-sized bits"[i] because “some seabirds eat so much plastic[ii], there is little room left in their gut for food, which affects their body weight, jeopardizing their health…. [and fragments of] sharp-edged plastic kills [the] birds by punching holes in internal organs". Alongside straws and lids, our shapes include several antiquities. In one majestic seabird you'll find a 3rd–2nd century B.C. bronze statue of Eros sleeping alongside a plastic spoon. In another, some of you might recognise the shape of a certain netsuke mouse (from Looped), and ornate columns from the hills and valleys of our artists’ book No longer six feet under. Something beguiling, we hope, but also something to make you think. We’ll see. It’s still all in process, and as logistical challenges arise, we need to remain flexible and quick-footed.

Included in our weight you will find a Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans), Southern royal albatross (Diomedea epomophora), Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis), Black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), Shy albatross (Thalassarche cauta), Grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma), Indian yellow-nosed albatross (Thalassarche carteri), Sooty albatross (Phoebetria fusca), and a Buller’s albatross (Thalassarche bulleri).

This is where we are so far. Nature. And our process.

Keep an eye on #AWeightofAlbatross to see this develop.

On Midway Atoll, a remote cluster of islands more than 2000 miles from the nearest continent, the detritus of our mass consumption surfaces in an astonishing place: inside the stomachs of thousands of dead baby albatrosses. The nesting chicks are fed lethal quantities of plastic by their parents, who mistake the floating trash for food as they forage over the vast polluted Pacific Ocean. For me, kneeling over their carcasses is like looking into a macabre mirror. These birds reflect back an appallingly emblematic result of the collective trance of our consumerism and runaway industrial growth. Like the albatross, we first-world humans find ourselves lacking the ability to discern anymore what is nourishing from what is toxic to our lives and our spirits. Choked to death on our waste, the mythical albatross calls upon us to recognize that our greatest challenge lies not out there, but in here.

— Chris Jordan, Midway: Message from the Gyre (2009 – current)

[i] ‘Nearly Every Seabird on Earth Is Eating Plastic: Plastic trash is found in 90 percent of seabirds. The rate is growing steadily as global production of plastics increases’, Laura Parker, National Geographic online, accessed 12th February, 2018.

[ii] “The effect of plastic ingestion on seabirds in particular has been of concern …. due to the frequency with which seabirds ingest plastic and because of emerging evidence of both impacts on body condition and transmission of toxic chemicals, which could result in changes in mortality or reproduction. Understanding the contribution of this threat is particularly pressing because half of all seabird species are in decline. Plastic pollution in the ocean is a rapidly emerging global environmental concern, with high concentrations (up to 580,000 pieces per km2). Seabirds are particularly vulnerable to this type of pollution and are widely observed to ingest floating plastic.”

‘Threat of plastic pollution to seabirds is global, pervasive, and increasing’, Chris Wilcox, Erik Van Sebille, and Britta Denise Hardesty, 'Proc Natl Acad Sci USA', issue 38, 22nd September, 2015.

Sands of time: The North Sea is rich in signs of what made the modern world. It’s also a monument to what awaits us in the Anthropocene, David Farrier

Royal Albatross Conservation’s Royal cam: Live stream and highlights, New Zealand

Royal Albatross Centre, Otago Peninsula, Dunedin, New Zealand

Plastic in Albatross Chicks at Midway Atoll, National Wildlife Refuge, Jaymi Heimbuch

Image credit: Albatross at Taiaroa, photographed by Sabine Bernert; sourced: Department of Conservation, Te Papa Atawhai, New Zealand